Jules Andre Destrigneville

(1889-1977)

Below article was featured in Great War Group

Salient Point Magazine#5: Africa

The French army is often forgotten on the Western front by English speaking observers, due to the heavy focus on the British sectors. That does not mean that we should ignore or forget the sacrifices French soldiers made on their home soil.

So what did the average French soldier experience during the war, what was their war like? To help me I have a primary source of regular letters and postcards from my Great Grandfather, otherwise known as Sgt Jules André Destrigneville. Jules endured 1178 days of war starting in late August 1915 until 11th November 1918, via Auberive, Tourbe, Massiges, Verdun, Baccarat, Soissons, Sambre Canal, but he also experienced the nuances of the French Army way of life: the terrible pay, insufficient equipment, inedible food, monotonous routine, absence of empathy from senior officers, unjust leave system and above all horrendous living conditions, that impacted soldier health and morale on a daily bases.

Born on the 23rd June 1889 at Fouchecourt in the Vosges. Jules early years, like all able-bodied men of the period was influenced by his military service, which was compulsory in France until 2001. Jules started his military service with the 79e infantry regiment in Nancy in 1909, where he would spend his next 4 years, quickly rising through the lower ranks to “caporal” in November 1911. After his military service in 1912, he naturally transitioned to become a Gardien de la Paix (policeman). Little did he know that this choice of career would most probably save his life, when general mobilization was announced in August 1914, policemen were (generally) exempt. Therefore, it was another 12 months before Jules was called up and arrived at Mamers (Sarthe department of France) on the 21th August 1915, the home of the 115e infantry regiment (315e infantry regiment being a reserve regiment of the 115e).

Training was very basic and a rushed affair (as fully trained soldier, this was purely refresher training), but its aim was to re instill discipline and for Jules it would reacquaint him with the French Army way of life, which was not necessarily conducive or the best way to motivate recruits before going to the front. Jules reports on 11th September that some of the recruits at Mamers were unfit for service and could barely walk. Therefore he wondered why the army had conscripted them in the first place, let alone sending them to the front.

Jules immersion started as soon as he walked through the gates of Mamers depot, where they had no new uniforms (bleu horizon) available and he would start training in his civilian clothes. When his uniform finally arrived in late August, one crucial part was causing him grief …. his ill-fitting boots. Despite this major issue for an infantryman, he was told in no uncertain terms that these were the only ones available, to which Jules’s solution, was to buy a new pair of non-military civilian boots in Mamers. Boots were not Jules only non-regulation piece of equipment, as in October 1915, he asked the Police to supply him with “une pelerine” (standard policeman cape) as the Army uniform provided no protection against the rain and let alone the cold. Therefore, all over France, families and friends became providers of warm clothes such as “tricot” jumpers and scarves, which gave each “poilu” their own unique look.

Such basic shortcomings and having to provide for yourself is actually a perfect introduction to the French soldiers way of life. However there was often another way if you could afford to pay, that was not just for improved equipment, it went as far as access to better meals. During training this practice was brought to Jules attention, where the Head of the Officers mess would allow non officers to eat for a small fee of 14 sous (French equivalate to pennies). As Jules mentions in late August 1915, it’s a small price to pay for superior food, with dessert, coffee and cider at every meal. Unfortunately Jules’s gastronomic meals quickly came to an end with his training.

His training, followed by a standby period that went on for a month and half, meant Jules and his fellow soldiers then played a waiting game to be called up to the front. Like many soldiers, their call up to the front would be triggered following tragedy. For Jules it would be the ill-fated Champagne offensive on the 25th September 1915, where Jules’s new regiment 315e, would have a front row seat. None would feel this attack more than his future battalion, the 4e, who on the 25th September at Auberive lost 9 out of 12 officers, which included the battalion commander Fernand Albert Henry (pictured below). The regiment itself lost 16 officers and an estimated 495 men, along with 846 wounded in 24 hours; such losses were not sustainable, and reinforcements were quickly required.

Jules arrived at the front in early October 1915, as a newly promoted Sergent, where he was thrown in with the 4e battalion to fill the gaps left by the previous week fighting. This is the place Jules would call “home” for the next two years. However his “new home” was a dangerous one and one false move or wrong decision, could have fatal consequences, but these were the daily dangers that all soldiers faced. Despite this, there was time for humour and camaraderie, where soldiers would laugh off their misfortune and poke fun at each other, until the next 77’or 105’ would fall. Then as Jules says “people’s faces would change in an instance when the shells and bullets begin to fly”.

Jules first letter from the trenches gives us an insight into sounds he was hearing as he wrote these letters:

“I am currently writing this letter from the second line trenches and the 75’ are passing overhead and I can hear them whistling through the air, the Germans are not responding. Today, we are in the 2nd line of trenches, but it’s even more dangerous than the frontline as we have no shelters”

6th October 1915

The final months of 1915 were spent in the Tourbe Sector in the Marne, where gas attacks became a daily annoyance, to which Jules managed to find a funny side in a letter from late October he says:

“Just as I was finishing your postcard, the boches decided to shower us with gas …… this is starting to make us feel unsettled, but luckily we are equipped with our cagoules, you would think it is Mardi Gras, but they are precious to us.”

November 1915

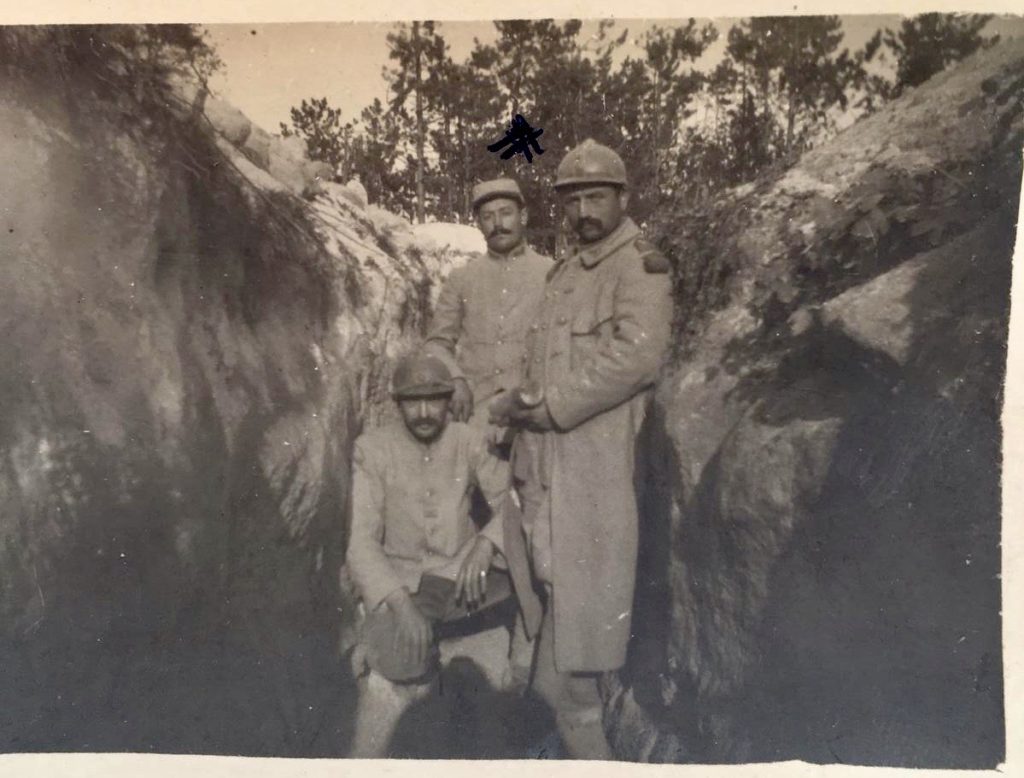

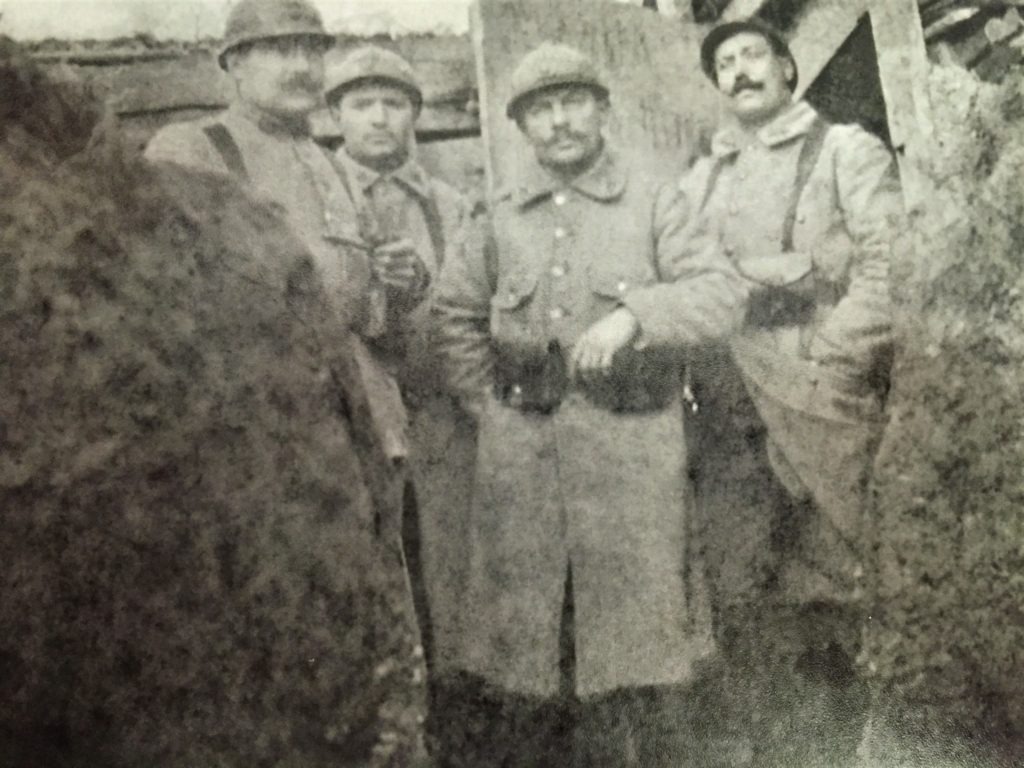

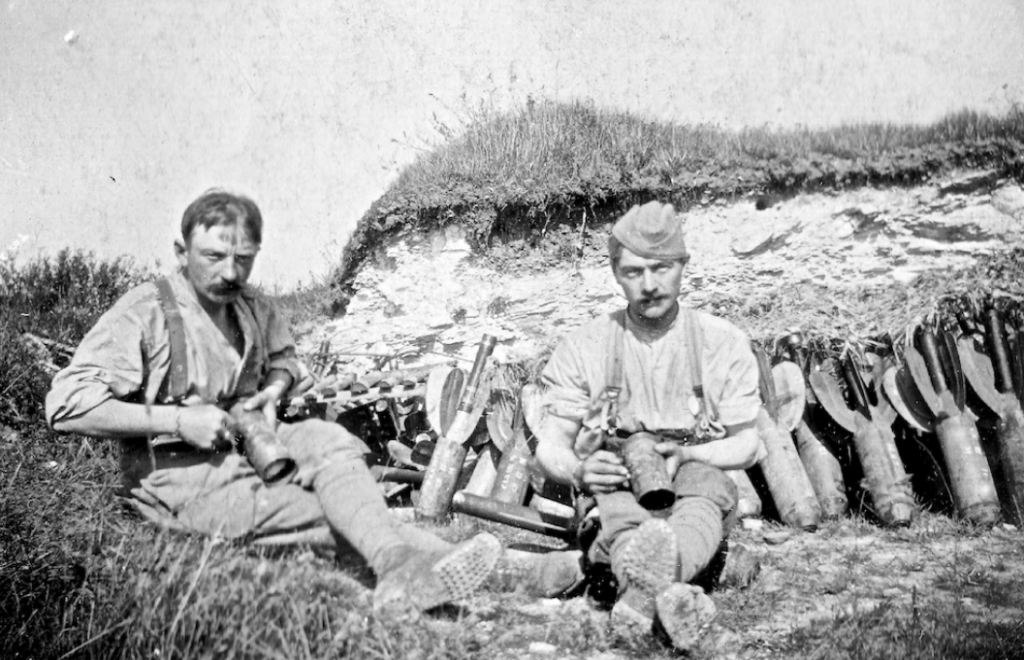

Below picture are of the 315e soldiers in the Auberive frontline in Oct 1915:

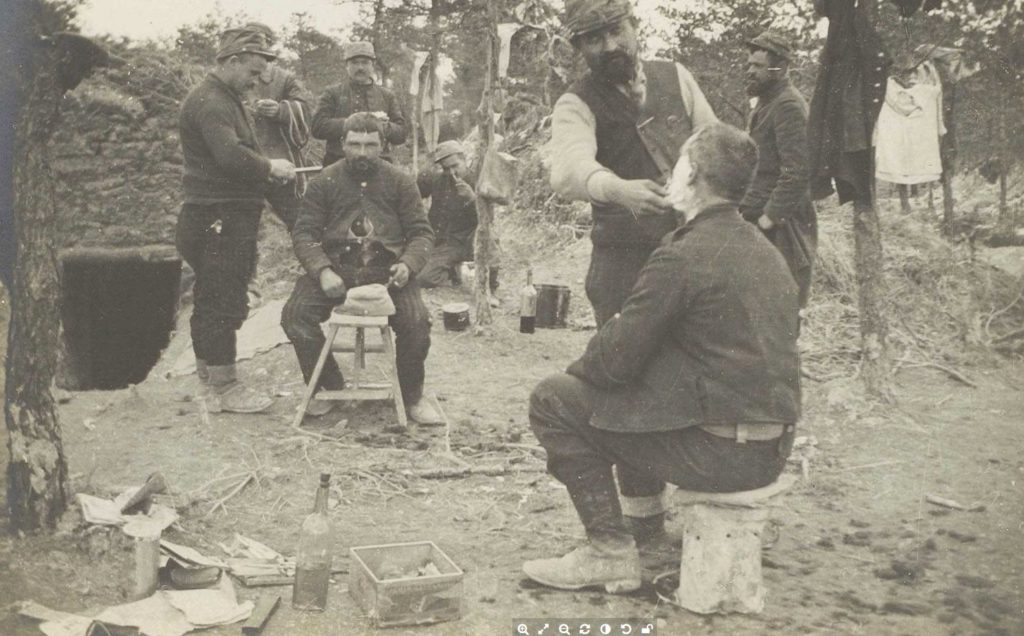

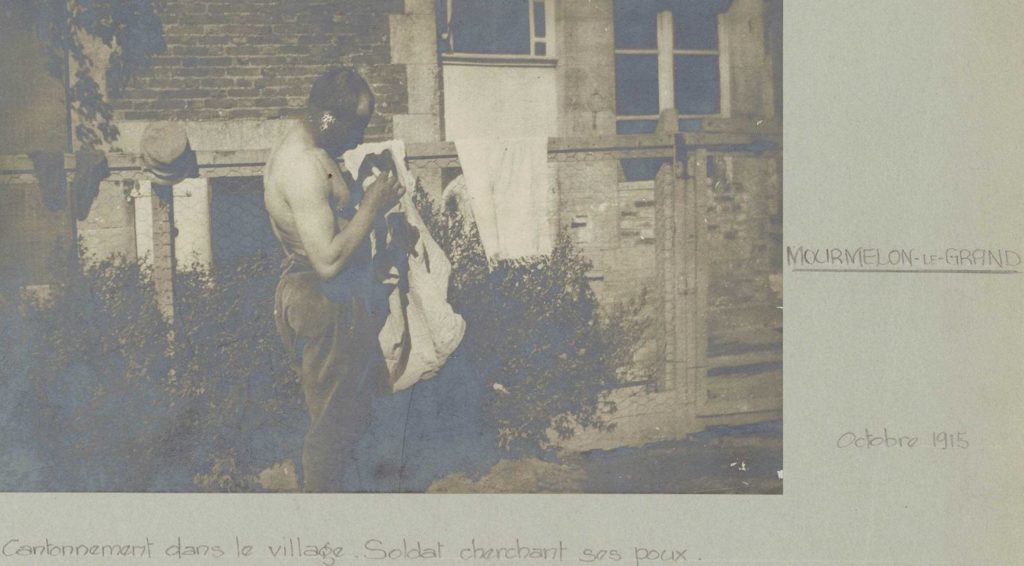

During this early chaotic adaptation period in the trenches, good hygiene was difficult. For Jules not being able to wash and shave for 12 days in a row was hard, as he was used to being well groomed. However, to his delight he comments on 6th October 1915 “we have an ex hairdresser in my section, so at least we will be able to have our hair cut and look smart”.

By late November good hygiene was a distant memory. After a period of torrential rain, many of the trenches collapsed, creating rivers of mud. To combat this, Jules and his men were given “bottes en toile” which were a type of galoshes. The men were very pleased as it kept their feet and shins a lot drier, however they found it near impossible to walk in them. On the 30th November Jules laments that it took him 1 hour to walk 200m, whilst fearing:

“I may get totally stuck and drown in this muddy hell hole”

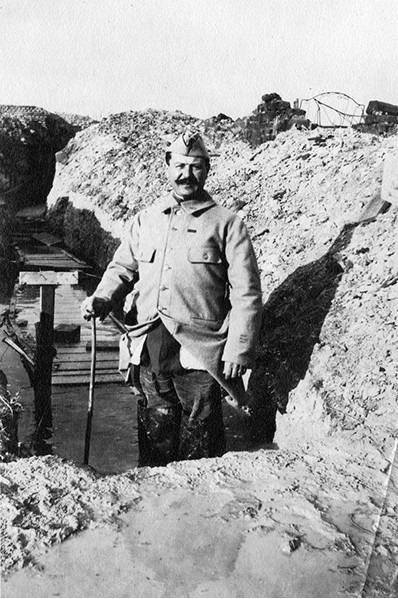

Below are photos of the 315e during November 1915 in the Tourbe frontline mud …

In December Jules writes home that he is now using newspaper instead of socks in his boots and jokingly says “it is the war and everyone finds ways to adapt to the situation”. At the same time he notes in a letter that it is the same for the Germans opposite them, who are currently in full sight of Jules outside their trenches, also covered head to toe in mud, repairing the walls of their trenches, however nobody fired a single shot. This highlights the respect shown at times in the frontlines, with both sides having to face the same challenging conditions and a mutual respect of collective suffering was seen by both sides.

After the initial activity of the first 3 months and being thrown in at the deep end, Jules admits he has started adapting to his soul destroying new life, which was a mix of boredom, followed by periods of intense activity and sheer terror, where sleep was now at a premium and came rarely without a background soundtrack of French and German artillery. The only link left to the normality of friends and family was the postal service which was a life line for Jules and all soldiers, regiments and the entire French army.

A question you may ask is how was the Christmas period in the trenches in 1915? Excellent question; there was no time for a Christmas truce in 1915 in Jules Sector, as on 25th December at 1am he received a present that many soldiers wished they would not be presented with, but it turned out to be his lucky day:

“I was coming back to my dugout when I was told the Lieutenant wanted to see me. I had done less than 10 paces down the trench, when a German 105’ fell directly on my dug out and smashed it to bits. I was a bit dazed, but not hurt …. What luck!”

25th December 1915

His Christmas present? His section got put to work on Christmas Day to repair the damage from the 105’ and Jules had to sift through the debris to find his shattered personal belongings, but concedes “I have had a very lucky escape”.

1916

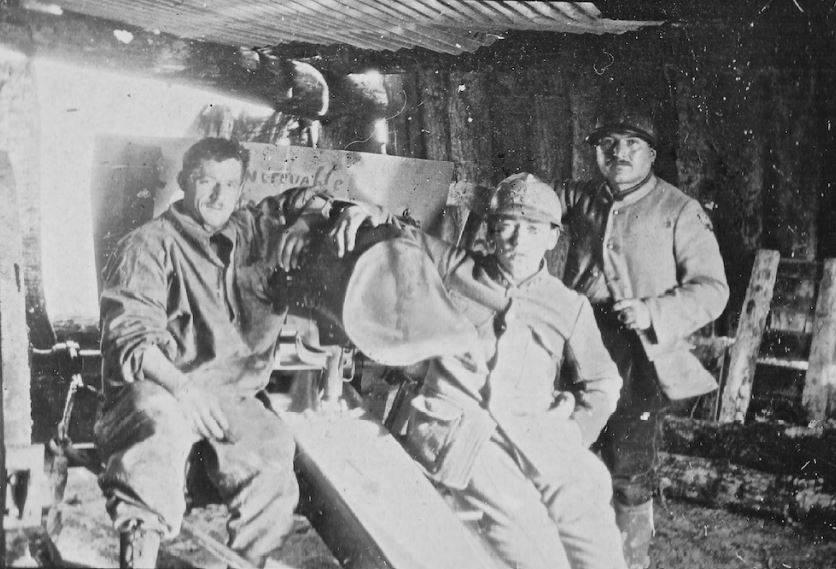

1916 arrived with a German artillery bang, but Jules and his fellow sous officiers managed some celebrations, which included a “warm” meal with a menu that incorporated trench names and a little concert amongst themselves as many of the sous officiers had hidden musical talents. However the celebrations were short lived and in early January 1916, Jules and the 315e were transferred to a little-known sector called Melzicourt (now called Servon-Melzicourt) which was a narrow arrowhead of a frontline surrounded by woods. The main features of this new sector would attract very few holiday makers even today, as the Aisne river, which provided fresh water, also created a swamp like terrain, which in turn created a unique battlefield. Trenches had to be built upwards rather than downwards, but one luxury, was that it was a fairly quiet sector. Unfortunately, that did not make up for the horrendous living condition, due to the waterlogged ground, that was made worse by the persistent cold and wet winter weather. The rain and mud were however “bearable” as Jules puts it, compared with one other feature of this battlefield.

One letter from February highlights the biggest worry of the regiments at the time, and it was not the German Army. During an evening watch on the 15th February, after another day of continuous rain, where their shelters and trenches where flooded and the water pumps broken, their real enemy appeared: “the trench rats”. The trenches were an ideal breeding ground and a daily pest to the soldiers, but in Melzicourt due to the flooding the ground was no longer their prime real estate. During the day and night these rodents would taunt sleeping soldiers by crawling over them. They would take shelter in whatever was available, which on the night of the 15th so happened to be Jules kit bag, whilst on sentry duty. They conquered, by nibbling everything in it including shirts, pants, socks. In a letter and moment of despair Jules comments « un de ces jours ils vont nous bouffer tout vivant » one of these days they will eat us all alive……

After the mud of Melzicourt, the 315e and Jules went back to Tourbe where the inclement weather followed them. One aspect that had changed was the German’s regiment opposite, who seemed to find a sense of humour, and decided to engage in psychological warfare with the French. Over a numerous number of nights, the Germans placed placards in no man’s land, which started as very basic one-word insults, but got more complex over time. One example from the 19th June read (French translation of the German):

“The Russian offensive has come to nothing. With us you can also be prisoners. Please come …”

19th June 1916

Not content with just a verbal assault on French hearts and minds, an additional caricature was added of a German soldier dragging a French cockerel along by a chain. The fate of the placard is unknown, but it is safe to assume it was quickly removed by the French…. It was not just placards that were needed to be removed in Tourbe, as Jules and his section struggled to get any sleep due to the infestation of “totos” fleas in the trenches. As Jules alarmingly writes in May “they are going to eat us all alive if it continues like this”.

After a short and itchy stay in the Tourbe sector, it was time to move onto Massiges and the Mont Tetu (the Stubborn Hill), with a quick 4-day detour in late June to Mourmelon to train and work alongside the newly formed Russian Expeditionary Corp (who Jules described as being very good). Jules spent 3 months in this hot and humid dust bowl of a sector known as Massiges, where they lived in vast underground shelters playing many games of Manille and Piquet (popular French card games).

Life in Massiges was made more challenging as his compagnie the 16e was disbanded and with little warning he was thrown into the 14e. Such a move was a shock to the system, but also showcased the huge differences even between companies in the same battalion. However, for the soldiers of the 16e, this change was not welcomed as Jules commented in late June

“So many changes, we are all very sad, we all knew each other and now here we are all with strangers, officers, NCOs. Well, what do you want, that’s life”

June 1916

The above is a stark reminder of how compagnies were extended families, but also how they were often ripped apart by events outside of their control. The pain of leaving colleagues and friends and having to rebuild bonds in other compagnies is an experience that Jules and all the men would rather not have to go through. Ultimately, it was not their decision to make, and this seismic change was exacerbated by senior officers who left soldiers for 24 to 48hrs or even longer without knowing their fate (staying with the regiment or being transferred out). All they had left was to “hope it would all be fine”:

“j’espère que là aussi cela se passera bien”

The new compagnie commanders however did not endear themselves to the newly arrived men by their mismanagement. Jules and his fellow transferred soldiers may have accepted some mistakes, but in this new compagnie one of the crucial life support to soldiers morale was completely broken: the postal service. For months on end parcels, letters, money orders, were late arriving and in some cases did not arrive at all. To add to that, the company leave process, was constantly changed and suspended for no apparent reason, leaving soldiers and even lower ranking officers in the dark over when their next leave would be. Ultimately responsibility was with compagnie commander Lieutenant Chenal to find solutions, but he seems more interested in bringing more unhappiness to his soldiers’ lives. During one back-to-back frontline tour (16 days straight) he banned his men from bringing up provisions such as wine and non-regulation food to the frontline …. This situation is made all the more ridiculous, when on the 6th August Jules writes that the bread rations they were given were now black like shoe polish …. And totally inedible ….

The officers on the other hand often ate better: couple of 315e example below from July 1915 with Capt Ferran and LTN Goulon share a glass of red. Top right LTN Goulon eating off a make shift table make of ammo boxes.

Such disdain did not go unnoticed from the men and these “second-rate” commanders met with the wrath of Jules’s pencil, who described the compagnie’s officers as “rudement rasoirs” (pretty irritating) and “presque nuls” (nearly useless). Such lack of trust and camaraderie towards the officers meant that the compagnie’s morale and resolve would be put to the test when their new orders arrived in mid-August. Their resolve was now to be put to its greatest test. Like many French soldiers, it was now Jules’s time, to go to V (soldiers called it V rather than Verdun).

His time at Verdun started in an unusual way as he found out his regiment was going there after finishing his leave in late August. As Jules then wrote on 1st September:

“Coming back to Verdun, there no better place to get back into the swing of things”

1st September 1916

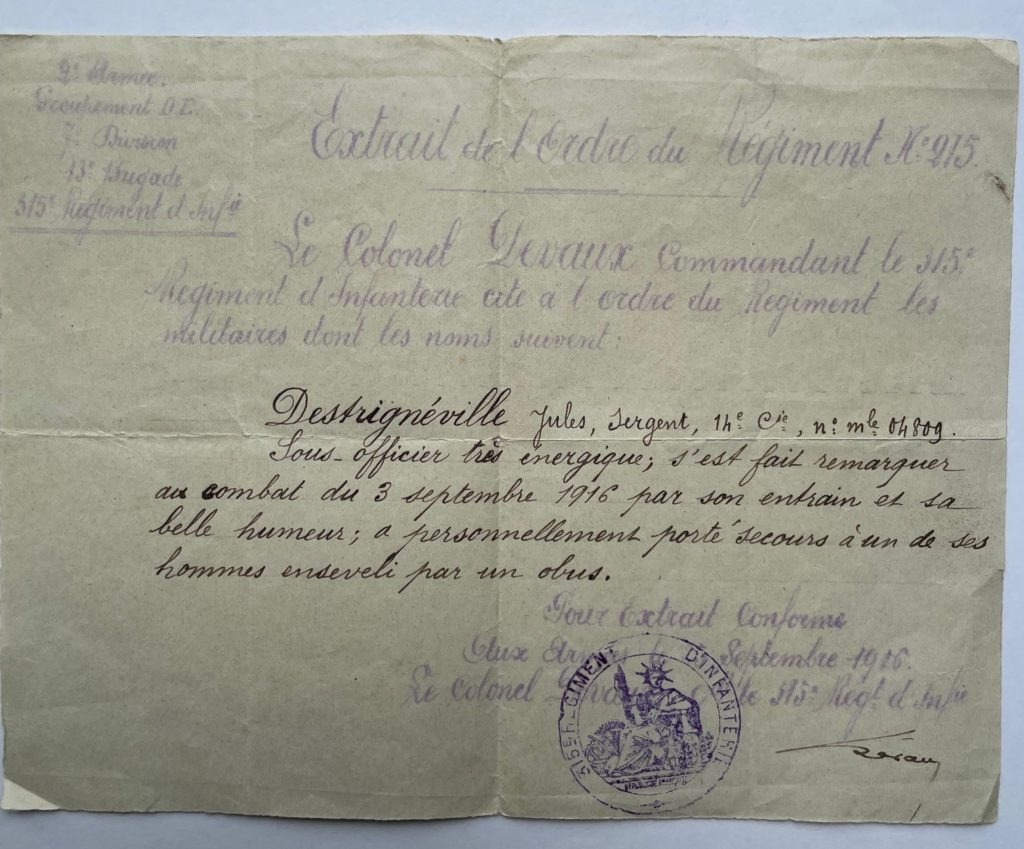

His words were ironically accurate as on the day he arrived back with his unit on the 3rd September 1916 he earnt his first regimental citation south of the ouvrage de Thiaumont, whilst supporting 102e attack at Fleury-devant-Douaumont:

“Destrigneville Jules Sergent,14e compagnie, matricule 4809. S-officier very energetic, whose actions were noted for his drive and positive attitude during combat of the 3rd Sept 1916, who personally rescued one of his men that had been buried alive by a shell”

Citation from 3rd September 1916

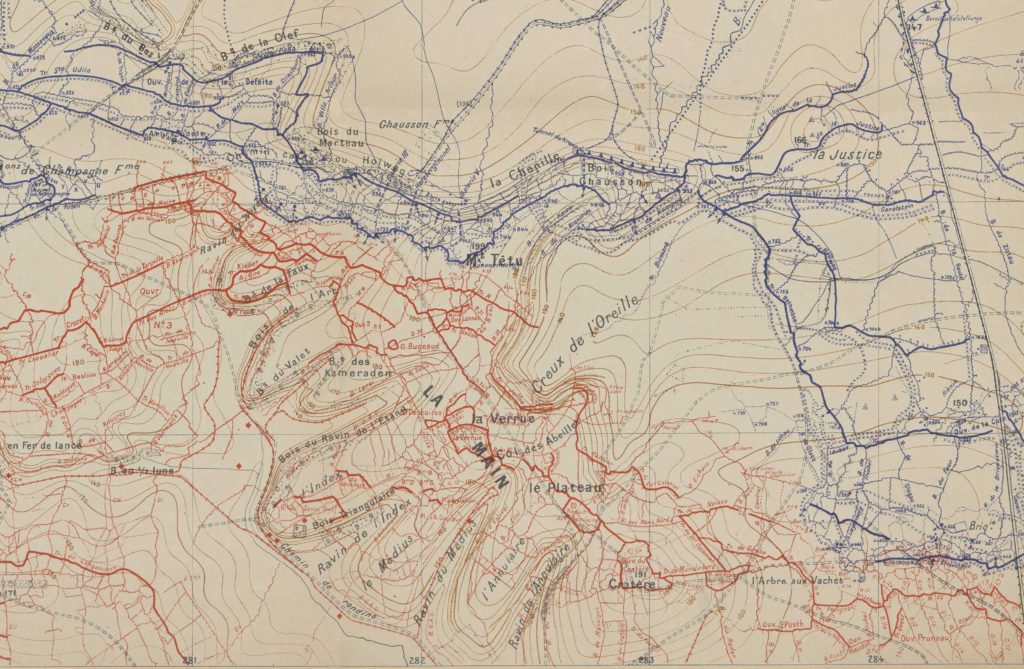

In September 1916 the French were on the front foot, but that does not mean Verdun had lost its aura as the furnace (name given because at night the glow from explosions made it look like a burning furnace). On the 6th September after a violent 9 hour bombardment (18,000 shells fired), the 315e went on the offensive for the first time since the disastrous offensive of 25th September 1915.

Jules and the 315e would attack the Germans near the ouvrage de Thiaumont, with the objective to capture Point 1599 and 1795, which were less than 100m from their frontline trenches. The term ‘trenches’ is used loosely here, as it was actually sections of shell holes connected together to form a frontline trench. Over this moonscape of a battlefield around 100 men died and well over 300 wounded (actual number could be far higher) for the measly gains of no more than 25m in places, which General Robert Nivelle on 15th September grimly noted:

“These were unacceptable losses, which were out of proportion to the minor initial objective. This was partly due to the grenade attacks having an objective of moving quickly, therefore being hard to coordinate with an initial bombardment, then a creeping barrage moving at 25m every 2mins. However, the infantry could not keep pace and therefore creeping barrage was ineffective. In summary, these three identical attacks (4th, 6th and 8th September) were poorly planned, poorly prepared and badly executed. Due to the losses that were out of proposition with the aims of the attack, the 7e Div commander (General Weywada) is to be informed to halt all such attacks and abandon such tactics in the future”

Below: Col Devaux (315e Regiment commander), LTN Durand and Capt Tassel who would all died at Verdun during the 315e two tour at the furnace.

However, as Jules wrote during his time there, for the ones that survived the horrors of these futile attacks, they would all lose something at Verdun, but not exactly what you would expect:

“What did we lose … that was body weight”

The Battle of Verdun was unique, the fortresses were a symbol to the French nation. Fighting had been raging since late February. After 8 months of continuous artillery activity, the landscape and terrain were inhospitable and far from ideal for creating human supply chains. However, knowing such constraints, better planning should have been put into place by September, but it turned out to be the opposite, with men sent to the “trenches” for 9 days with standard rations consisting of :

- 2 L of water

- 1x Sardines,

- 2 bread rolls

- 2x Canned beef

- 3 Grenades

- 200 rounds

- 1 flare

Such food provisions would normally last 2/3 days and would be supplemented by a local popote (mobile kitchen) brought up to serve hot food. However at Verdun the terrain and logistics could entail walking up to 5km under heavy artillery fire to get hot food, which was a risk not worth taking for many. For 14e compagnie and Jules, it meant surviving 9 days in the frontlines with their supplies and whatever else they could scavenge, which sometimes involved stripping fallen comrades or enemy bodies of food. However as Jules reports:

“it’s better to lose weight than leave your skin here…”

The horrors of Verdun are well documented, but reading Jules’s written words makes you wonder how soldiers managed to walk out of the furnace alive:

“all I can say is that I am still alive, nothing to eat or drink, but we carry on” 4th September

“I will have much to tell you once this war is over” 4th September

“What we are going through here is unimaginable days and nights in the rain without food” 5th September

“We have been totally forgotten … I can’t say anymore because I am afraid my letters may be read” 5th September

“A terrible bombardment, that lasted 9 hours … I thought I had seen my final hour, our hair will soon turn white. No food supply has come, we live on little ‘eau de vie” and a bar of chocolate, it is all we can swallow, bread cannot go down” 6th September

“I have never seen such horrific scenes” 8th September

“What a massacre and at times we cannot carry the wounded away” 9th September

“Losses are so high we have lost 1/3 of the company” 9th September

“We are covered in blood and flesh, people would mistake us for assassins” 11th September.

“For 8 days I slept sitting upright” 12th September

The above extracts from letters provide vivid images of the 9 days of sheer hell on the Verdun frontline, where soldiers became “ghost like figures” isolated from civilization, deprived of food and sleep, resulting in near exhaustion. The continuous heavy bombardments became a staple of these men daily routine. Jules himself refers to the boom, boom of the canons as “la danse recommence”, like a continuous beat from the gates of hell.

When looking at the artillery stats for the 7e Division, we can understand why Jules uses such a phrase for the continuous artillery beat in the background . On 6th September for example, 18,000 rounds were fired during a 9 hour bombardment. That means a shell roughly being fired every 1.7 seconds, which is likely why Jules thought he had seen “mon heure dernière“ his last hour. Whilst fellow 14e compagnie soldier Hervé Lambert described the landscape, as a moonscape filled with decomposing and shattered corpses, with a smell so foul, it stuck in your throat.

Below is a picture of Herve Lambert mentioned above, plus some pictures from October 1916 of the sector around Thiaumont and MF2 and Quatre Cheminees, where Jules and the 315e attacked on the 6th September 1916:

Thankfully the Verdun experience was over for now and the regiment was sent back into reserve for a month long rest period. When we use the words “rest period”, we assume that soldiers were having a quiet and relaxing time … in the French Army it was far from it. In numerous letters, Jules complains that they are spending more time at work and training than when they are in the trenches. Often during these periods it was the right time for a solider to discover “new skills”, which had an additional benefit of extra francs in their monthly pay check! During his time with the 315e Jules became a qualified signaleur by learning morse code, and much to his delight it meant that he would often be allowed to skip the compagnie exercises. Exercises could be literally “exercise” i.e. route marches, all the way to full battle planning and coordination between infantry, artillery and air force. However soldiers would gladly put their hand up to find ways to miss exercises. One such exercise was on the 1st June 1916, where Jules and his compagnie were taken to a cave; sealed inside and gassed to try out a new type of gas mask (model is not noted but likely to have been ‘TNH’ Mask (issued as from April 1916) or the 2nd pattern M2 introduced at end of July 1916). Lucky for them they worked!

During quieter times soldiers would turn their hand to Trench Art, which they made mainly from left over material and Jules himself would make rings and send them to family and friends back home.

The month of “rest” quickly came to an end in late October 1916 and the regiment was on the move again. The hope was a return to Champagne, but many accepted they may have to go to the Somme region. However, many did not expect to be sent back to the furnace they had just survived. Soldiers and officers alike were unsettled by the news, but for many the hardest part would be to communicate this back to their loved ones at home. By this time loved ones knew of the horrors they had just survived through letters and newspaper reports. Therefore when Jules announced he would be going back to Verdun on 22nd October, he saw the need to add a flower to his letter when breaking the news, which remarkably has survived 105 years later:

“I have survived Verdun once I will survive it again”

Verdun would also be the final action of 1916 for the 315e as they stayed in the area until December. Arguably their time there in late October/ early November was more miserable than September, due to the hardship they faced in reserve lines, digging trenches and horrendous weather. The regiment suffered a high rate of attrition from trench foot, frost bite and illness:

“There is so much mud here, we can’t recognize each other” 24th October

“Meat arrives to the trenches in bags dragged along in the mud …… the bread as well, that is all we have to eat, we are starting to look like ghosts” 31st October

“My head is pounding with all these shells falling. We are suffering more from the shells falling than from the cold ……” 13th November

Jules’s letter from October was correct, he survived Verdun, but this time he would leave on a stretcher as he was wounded on 14th November to the North West of Fort Douaumont by an exploding shell, where he sustained a broken shoulder and would only return to action in March 1917 in Baccarat, after over a month in hospital in Neufchateau.

The carnage of the war continued for Jules until 11th November 1918 when the war officially ended for him in the fields of Belgium, 1178 days after his mobilisation in August 1915. The world they knew had changed and many would now come back home to no job and be physically and mentally scarred by the war. Jules was lucky as he could swap his Adrian helmet for a his policeman kepi and his whistle could now be used to direct traffic rather than men over the top.

Unfortunately, we end the story here for Jules, but it is also a moment to pause, remember and reflect on the sacrifices that millions of ordinary men like Jules made, plus the estimated 1.3 million Frenchmen that made the ultimate sacrifice for France and would never come home.

![]()